|

Karen and I followed the Torrens River bike path which got us out of town easily and scenically. We climbed up into the hills again, through Houghton and Inglewood to lunch in the Chain of Ponds cemetery, then it was on through Williamstown to Tanunda. In the evening we walked into town for a pub meal of a mixed grill and chips, with a carafe of cheap red wine and a really nice waitress.

Before we left Tanunda the next morning, Karen spent about ten minutes squatting next to the bike while she cleaned some dirt from the chain and re-lubricated it. When she finally stood up, she felt a strong pain in her knee which did not go away, even after we started riding. We had booked a tour at the famous Seppeltsfield Winery and had given ourselves plenty of time to ride there, but the pain in her knee slowed Karen down and almost had her in tears. Despite my heartless threats, encouragement, complaints and cajoling, Karen's speed did not improve, and we were only just in time for the tour and subsequent tastings.

We lunched in the grounds of the beautiful old winery, then rode out through Greenock to Kapunda, stopping for photographs at the "Map Kernow" statue - dedicated to copper miners from Cornwall - just outside the town. Karen was in pain the whole time, but there did not appear to be anything wrong with her knee bio-mechanically. There was no need to push further, however, so we called it a day at Kapunda after only thirty four kilometres. We walked into town from the caravan park, discussing the injury situation. For the first time we were faced with the real possibility of prematurely finishing our trip. Karen felt that if we took things easy she might be able to continue. She did not want to end the trip, but she did not want to permanently damage her knee with lots of heavy riding either. We would have to play it by ear.

With an afternoon to kill, we walked into town to do some shopping, and regaled a bottle shop proprietor with tales of our adventures so far. He was so incredulous and impressed that he made us an offer we could not refuse - an extra bottle of champagne for only a dollar!

A southerly breeze sprung up overnight, bringing with it a very cold morning and an excellent tailwind. The trip from Kapunda down to the Barrier Highway at Tarlee was one of the best downhill rides we have ever done - long and gradual, with the cold, following breeze pushing us along at over thirty kilometres an hour. We hardly had to pedal at all. This allowed Karen to warm up her knee slowly before the heavier riding began. By morning tea the pain in her knee had reduced significantly, and it improved throughout the day. Although she would experience pain in the knee for many weeks to come, Karen's riding ability or speed would not again be seriously curtailed. Sometime in the next couple of months - these things are always difficult to pinpoint - the pain in Karen's knee disappeared altogether.

At least the pain had given Karen something to think about. At various times when we were riding I would call out to her to tell me what she was thinking, knowing that Karen's thought processes are not only different to mine, but possibly to everybody else on the planet as well. In the end, the question became a great source of embarrassment for Karen, because her answer was always the same. Food. It soon became apparent to me that Karen thinks about lunch all morning, about dinner all afternoon, and about breakfast all night. She wants to think about other things, however. Sometimes she would even beg me to think of something for her to think about, but thoughts of food would always push the new thought aside and take their accustomed place in the forefront of Karen's mind.

Karen believes that while she is awake she must eat at least once in every three hours, otherwise she will die - immediately and very horribly. As the end of the third hour approaches, every fibre of Karen's being becomes attuned to her impending demise, transforming her into an organism with only one objective - eating. When Karen is hungry, all else becomes secondary. If Tom Cruise or Richard Gere or Sean Connery or Mel Gibson walked past stark naked and offered himself to a hungry Karen who was about to tuck into a pack of Tim Tams, Karen would decline the offer and eat the biscuits. First.

Perhaps I am being a little too harsh. Our division of labour meant Karen was responsible for shopping and cooking, so it was natural for her to be thinking about the next break and what she would need to prepare, or the next town and what supplies we needed, or the next meal and how it could be improved. But every breakfast was the same as every other breakfast, every lunch was the same as every other lunch, and there were only six different dinners on our usual menu, so how much thinking does it take?

Shortly after leaving the highway north of Tarlee, I noticed a wallet lying on the side of the road near a rest area exit. When we were riding, Karen was usually too busy thinking about food or watching the scenery to notice things on the side of the road, but I was always finding stuff. We would be riding along, I would spot something, and I'd call out to Karen, "Just stopping for a second - I'll catch up!" By this time I would usually have passed whatever it was I had spotted, and would turn around and return to it, pick it up and check it out. If it was worth keeping, I would put it into my handlebar bag or tuck it under an octopus strap and ride like hell to catch up with Karen again. There is a lot of rubbish on the side of Australian roads, and I have checked out most of it. Occasionally, though, there would be something of value, like the wallet.

While Karen cycled off into the distance, I picked up the fat, heavy wallet and quickly stored it away without looking inside it. I did not tell Karen about it right away, but for about two hours I had a fascinating mental battle with myself over what I should do with the wallet. The good part of me was saying "Be honest, find out who it belongs to and send it to him." The bad part was saying "Don't be ridiculous. You're on a budget. There could be hundreds of dollars in this wallet. Think about how many days that will support you!" Unfortunately, I have an honest streak, which has disturbed Karen at times but which has always held me in good stead. The outcome of my internal battle was really a foregone conclusion, although it had been interesting listening to my darker side. I decided that it did not matter who the wallet belonged to, or how much it contained. I would post it back to its owner, using the money in the wallet, if any, for postage. I have lost wallets in the past, and I know how good it made me feel when one was returned intact. Perhaps the owner of the wallet I found would one day do the same for yet another person, and so the cycle would continue.

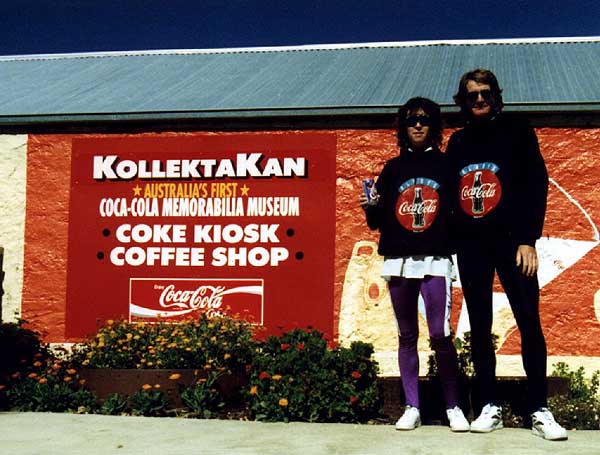

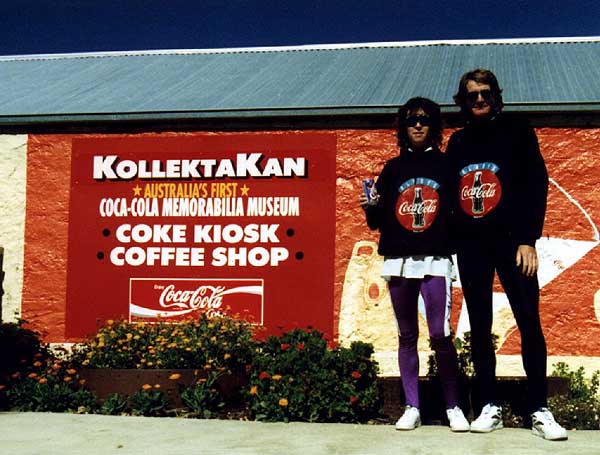

My deliberations were interrupted by the town of Auburn where a Coca-Cola Memorabilia Museum attracted our attention. With Karen being a former Coke employee, we could not pass the opportunity by, so Karen and I donned our Coke sloppy-joes and walked inside, hoping for a free tour. Unfortunately it did not happen, so we paid our two dollars each and took the tour anyway. It was excellent, and much better than the official Coca-Cola museum beside Circular Quay in Sydney. I even bought a can of Cherry Coke, usually unavailable outside of America but specially imported by the museum owner. It tasted okay, but if I never have another one I will not die heartbroken. Our photo album now contains a classic shot of Karen and I dressed in our Coke clothes carrying a can of cherry Coke and a couple of Coke water-bottles outside the Coke museum.

The Coca-Cola Kids

When we stopped for lunch, I had a look at the contents of the wallet I had found earlier. Ten dollars in coins was the reason it was so fat and heavy, and a learner's permit showed it belonged to a young guy from Gladstone named Noel. As we would be passing through Gladstone in the next day or two, I decided to deliver the wallet personally.

We spent the evening at a caravan park just outside of Clare where we met three fellow cycle tourers - Tom, who was going our way, and another couple who were headed for Adelaide. The latter told us of a great place to stay if we were going anywhere near Gladstone - the gaol! The gaol is no longer used for incarcerating prisoners, but instead is in the process of being restored by a local historical society. The restoration is financed partly by gaol tours, at a cost of three dollars, and partly by renting out cells for overnight accommodation. Four dollars would buy us our own private cell and the run of the kitchen, library, cell blocks, guard towers and exercise yards. They have hot showers and good facilities as well, so the next day we headed for Gladstone. Tom travelled separately but the three of us had arrived in town by mid-afternoon. We rode up to the gaol - about a kilometre from the centre of town - and arranged our stay.

After wheeling our bikes into our respective cells, Karen and I walked back into town to return the wallet. The address on the learner's permit was actually a shop, so we asked the lady behind the counter if Noel was at home. She explained that he was in Adelaide, and that she was his mother. I handed over the wallet, telling her all the details about where it had been found. She thanked us, and we walked out, but a few moments later she ran out in the street after us and asked for our address, so Noel could send us a thank you note.

The gaol was great. The historical society staff left in the evening, locking Tom, Karen and I in for the night. We wandered the corridors, climbed up to the top of the guard tower and inspected a cell which housed stills from a Bryan Brown film called Stir which had been shot at the gaol. Never had we felt so safe! Karen and I slept in neighbouring but separate cells, the only time we would sleep apart in all of our travels.

Karen in her cell

When talking to Kevin a month later, we learned that a package had arrived for us in Sydney - from Noel. When we finally arrived home in Sydney many months later, we found a thank you card and a whole pile of souvenirs of Gladstone - probably worth more than the contents of the wallet. We suspect that Noel's mother had a hand in the gift, but it still made Karen and I feel all warm and fuzzy that we had done the right thing.

The best thing about our night in Gladstone, however, was when we rang up Karen's mum and dad and told them we were in gaol.

|