|

The town of Derby is situated near the southern end of the King Sound, over one hundred kilometres from open ocean. For various reasons that I do not know, the sound and surrounding ocean combine to produce the second largest tidal range in the world. Our first day in Derby occurred at the time of a full moon when the tides would be at their greatest.

Derby is built just above the high tide level of the sound. During king tides, a couple of times a year, the town is surrounded on three sides by water, but for most of the year this area is a flat plain of cracked mud known as the Marsh. The Derby Wharf is located at the edge of the Marsh, a few kilometres north of the town, and it is reached by a long, low causeway. The first morning Karen and I were in Derby we walked out to the wharf to have a look at Derby's famous tides.

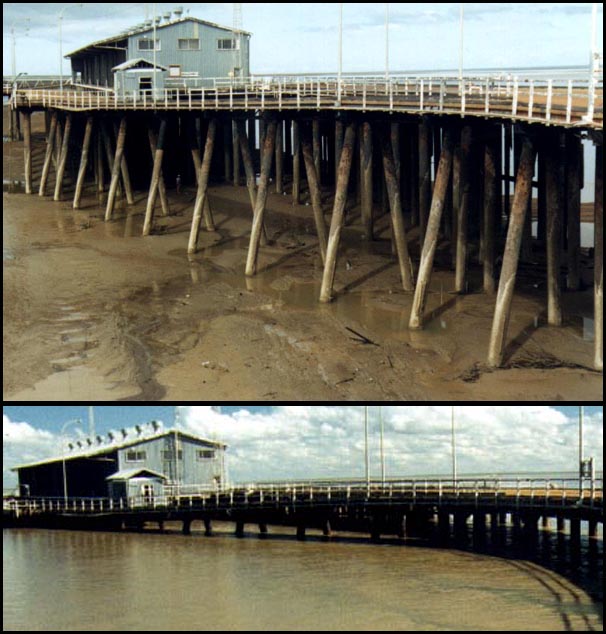

We arrived just after nine o'clock to find the tide almost completely out. I took three photographs of the wharf - a long semi-circular affair with two land accesses - which was high and dry a dozen metres above a floor of soft mud. A broad channel just beyond the furthest edge of the wharf contained brown water flowing slowly out towards the sea, but the water slowed as we watched, came to a complete stop, and seconds later began flowing back in.

Karen and I watched with total fascination as the flow increased, filling the gutters, grooves and depressions in the mud at an accelerating rate. The rising tide passed the footings of the wharf, the water's edge moving inexorably up the muddy bank. A quick calculation concluded that the tide was rising at about one inch per minute. In half an hour the water at the base of the wharf was already almost a metre deep.

Because Karen and I had no intention of watching the tide for the whole six hours it would take to reach its maximum height, we had arranged a variety of activities to while away our time. We retired to the shade of a warehouse on the wharf to each write a postcard to distant friends, before checking out the tide again. We then spent fifteen minutes speaking to two aboriginal women who were fishing from the southern end of the wharf for mud crabs. Afterwards, Karen and I grabbed the binoculars from our day packs and walked through the boggy mangroves which lined the sound, looking for birds. Three new ones joined our list - the Mangrove Whistler, the Dusky Gerygone and the Yellow White-eye!

We returned to the wharf to check on the progress of the tide and talk to a few local fisherman, none of whom were having any success. By mid morning the air temperature was well into the thirties, so Karen and I returned to the shade to write another batch of postcards. At midday we watched the tide again, amazed now at the speed of the incoming water. The sound had turned into a huge river of flowing water that no human would have been able to swim against. Not that they would have wanted to, of course, given the viscosity of the muddy water and the probable presence of potentially man-eating saltwater crocodiles.

At midday we checked the tide again and walked to a restaurant at the northern end of the wharf where we bought a lunch of fish and chips and Caesar salad. The latter was a bit of extravagance, but the occasional treat dramatically improves the quality of our travelling. After lunch we returned to the wharf to talk to other tourists and more fishermen. The six hours of incoming tide were almost over, with muddy swirls of water and floating debris showing that the tide was again about to turn. We returned to the spots from which we had taken our "before" pictures to photograph the afters, and were totally amazed at the transformation that had taken place.

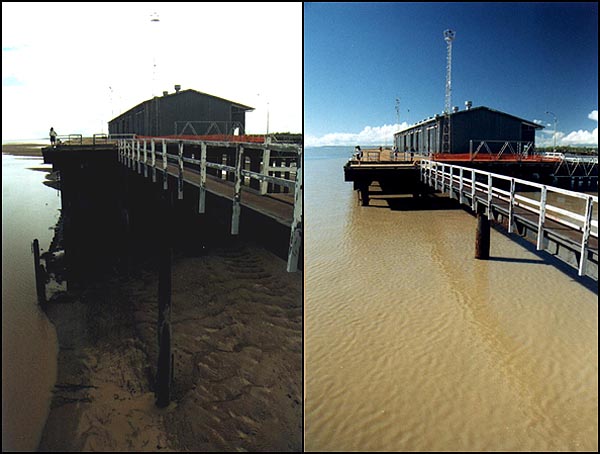

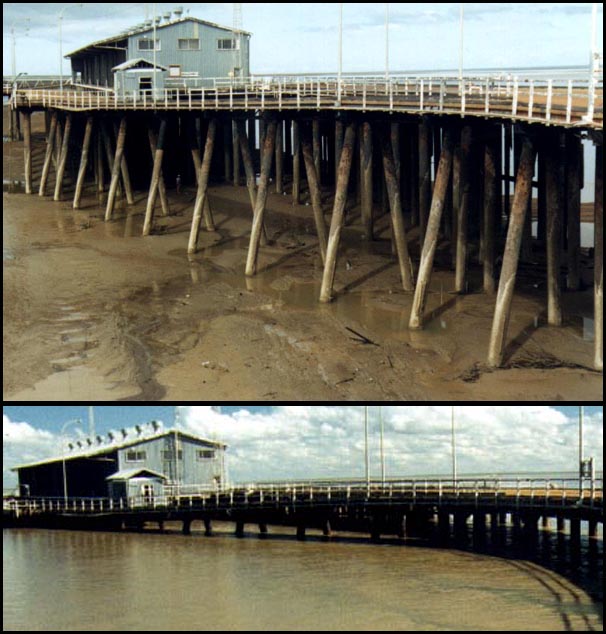

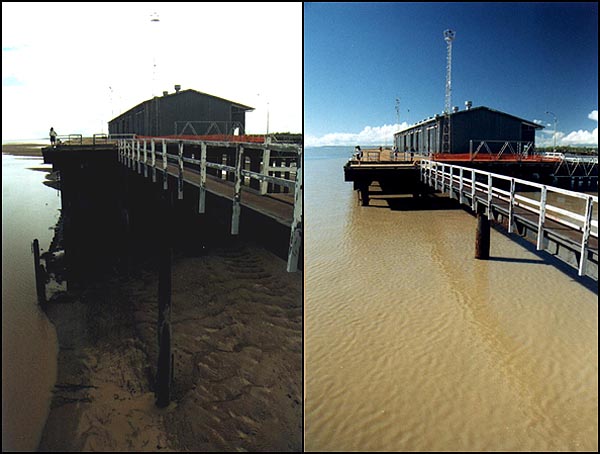

Before-and-after photo of Derby's amazing tide

The spindly structure supporting the elevated wharf was now almost completely submerged. Brown water lapped at the pylons only a metre below the walkway. The tide had risen almost ten metres, enough to submerge a three storey building! It was one of the most amazing things I had ever seen and a definite contender for the highlight of 1997.

Another tide before-and-after shot

There is something about the rising and falling of water that fascinates me. When Karen and I were in Townsville I had spent an enjoyable hour watching its ocean pool beginning to fill after it had been cleaned. Karen had to drag me away. Now I would have been quite content to stay at the wharf until nightfall, watching the tide run out, but Karen had seen enough. We stayed just long enough to watch the water slow, stop, and begin flowing out again.

Yet another tide before-and-after shot

King Sound is roughly rectangular, about a hundred kilometres long by fifty kilometres wide - an area of five thousand square kilometres. As one square kilometre is a million square metres, the area can also be described as five thousand million square metres, which is the same as saying five billion square metres. A rise in the water level of ten metres over this whole area gives us a volume of fifty billion cubic metres. This equates to fifty billion tons of water. Because this weight of water moves into King Sound in only six hours, this means that about eight billion tons of water per hour enters the sound. This can also be expressed as about one hundred and thirty million tons a minute, or over two million tons per second! Bloody awesome!

On the way back to the caravan park we bought a couple of spare tubes and a new bike chain for Elle. I was attempting to get the chain working properly when Peter, Mihkala and their dog Mac paid us a surprise visit. They had received our message and had come into town to see us. Over dinner we all discussed our plans for the immediate future. Peter and Mihkala were working as woofers about nineteen kilometres out of town along the Gibb River Road on a property called Birdwood Downs. It was run almost single-handedly by Robyn Treadwell, who had won the 1995 ABC Rural Woman of the Year award. A lot of work around the property was done by a shifting population of woofers and backpackers, and Robyn had said that Karen and I were quite welcome to come and stay for a while. We decided to accept her offer.

Peter also suggested that all four of us should take a scenic flight. Ever since his childhood - not that long - Peter had had a desire to see a famous Kimberley attraction known as the Horizontal Waterfalls, where the effect of the tides on a couple of inlets separated by narrow openings in a pair of parallel coastal ridges, causes water level differences and the formation, as their name suggests, of horizontal waterfalls. These could be seen on a variety of scenic flights, from a half hour jaunt costing less than one hundred dollars, to a four hour epic which included half of the Kimberley and offshore archipelagos for two hundred and seventy dollars.

Karen's mistrust of small plane trips and fear of air sickness made her vote for the shortest flight, especially when Peter mentioned that he had become car sick while travelling into the Bungle Bungles on a similar tour to the one Karen and I had done, and that both he and Mihkala had very little experience of small planes. Karen argued that given the possibility that she and Peter might get air sick, and maybe even Mihkala and me as well, the shorter flight was the sensible option. However Peter and Mihkala were very gung-ho about the four hour special and were willing to take the chance. Karen agreed reluctantly, but suggested that if the flight was booked by more than the minimum number of people, she might give it a miss. If she was needed to make up the numbers, then she would go. All four of us also agreed to go on a three day trip together in Peter's Kombi the following week, up the Gibb River Road to Windjana Gorge and Tunnel Creek.

The next morning, despite a lot of fiddling and mess, I could not get Elle's new chain to work properly. It is always recommended that the rear sprockets be changed at the same time as the chain, but because Derby did not have a bike shop to sell me the new cluster, I replaced my old chain and returned the new one. I could always buy these parts in Broome or Port Hedland.

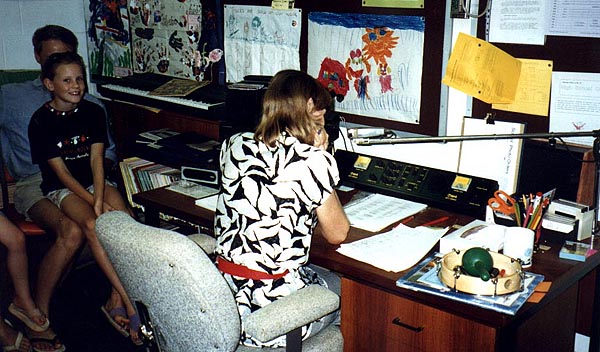

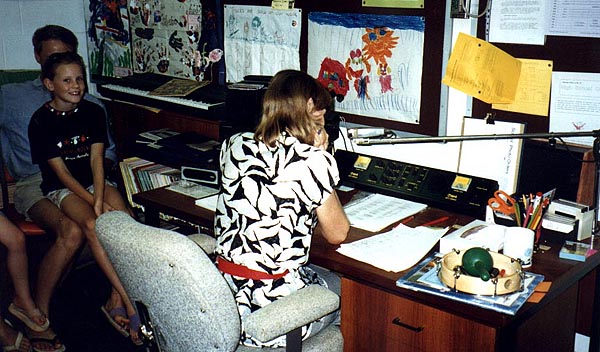

Karen and I did a couple of final tourist things prior to leaving Derby. We visited the School of the Air and spent forty five minutes sitting in on an art lesson for four to seven year olds, then heard a talk and watched a video at the Royal Flying Doctor Service. Afterwards, Karen shopped while I waited outside talking with a couple of local drinking identities, then we packed up the tent and rode out to Birdwood Downs.

The School of the Air

Hordes of hungry mozzies and a jogging Mihkala greeted our sunset arrival. Peter showed us around, introducing us to Robyn Treadwell and her ten year old son Matt, and woofers Nathan and Katrina. Robyn had built a dozen small huts for accommodation, and was hoping to establish a tourist business on the property. In the meantime, the huts were used by the woofers, and itinerant cyclists. Peter also showed us the similarly styled shower and laundry building which housed a massive population of green tree frogs and nondescript little brown frogs. At least fifty pairs of amphibian eyes looked down upon us from the ceiling and walls of the shower cubicle. In the days ahead we would also discover that frogs have a bad habit of urinating when they are startled, and sometimes even when they are not, and often our showers were prolonged by the additional washing required when the frogs scored direct hits.

Over dinner we learned more about Robyn and the property. Standing only about five feet tall, Robyn has a wiry physical strength and a determined, even driven, personality. She had been associated with the Bio-Sphere project in the USA, where a group of people were placed in a sealed environment for a year where they produced their own food and recycled their own waste. In a similar fashion, Robyn had made Birdwood Downs as organic and self sufficient as possible. Spread over five thousand acres, the property produces pure seeds, hay, cattle, bananas, eggs, pigs, white peacocks and watermelons.

For most of our first full day at Birdwood Downs, Karen and I worked with the other woofers in a paddock at the back of the main house where a field of watermelons was rapidly decomposing on the vine. A recent wet spell had caused the melons to split. They were lifted individually into barrows and wheeled to the pig pen where they were unceremoniously dumped on a large, disgusting pile of rotting watermelon. It was not exactly pleasant work as the melons tended to fall apart under their own weight. Even the pigs were beginning to turn their noses up as more and more melons were added to the pile.

With all the melons removed we set about clearing the old vines. The paddock was set up with lines of hoses, each hose punctured by regularly spaced drippers that slowly fed water to the plants, one plant per dripper. In the spirit of recycling, most of the equipment had been used before and much of it was damaged. In addition, the technology itself was highly suspect. I don't think it worked too well even when the equipment was new.

After Peter had okayed it, I also spent an hour or two swapping his bicycle seat post with Karen's. We had never quite got her seating position perfect, and after long days in particular she often suffered with a sore back. The design of her seat post had prevented me from repositioning the seat further forward to alleviate the problem. I had changed my seat post for the post from my old Malvern Star shortly after buying the bikes, but Karen had persevered. Now that I had the opportunity to fix the problem, I jumped at it.

In my diary I wrote that changing the seat posts was "a procedure complicated by slightly different diameters which could still prove to be a problem". These words would be rather prophetic, not for Karen's bike, because Mel accepted the new seat post without a qualm, but for Peter's bike, which steadfastly resisted the change. It was only after a great deal of twisting, turning, pushing, swearing and sweating that I managed to get Peter's seat back into its normal position.

The strain of running the property by herself might have been telling on Robyn, because when she had to entertain unexpected guests who dropped in late that afternoon, she neglected the food supplies for her woofers. Robyn was not obliged to cook for us, but the deal was that we worked and she provided food and lodging. When we went back to the communal area of the main house that evening, there was not enough food in the kitchen to make a meal. Karen and I, and Peter and Mihkala, augmented the meal with food from our own supplies.

Mozzies were in plague proportions both inside and outside the house. The communal area was screened, but the screens were old, sometimes ripped, and there were gaps between the top of the walls and the roof anyhow. Nights in the main house became a constant battle between man and beast amongst wisps of ineffective smoke from two or three mozzie coils scattered around the floor under the main dining table. One girl backpacker was eventually forced off the property because of mozzie bites, the parts of her body she was able to show us covered in scores of ugly, raised welts.

Our second day at Birdwood Downs was the scenic flight day. Our scheduled flight time was 9am, the morning flight recommended because the ground should not have heated up enough to produce the thermals that made for a bumpy flight. Karen had only agreed to fly if Derby Air Services had not found extra people, and they hadn't, so she became a reluctant passenger. She questioned the pilot at length about the possibility of air sickness, and what could be done to avoid it, and whether we could get our money back if we had to abort the flight. The pilot suggested a simple change of plan, saying that instead of flying in a clockwise direction when most of the early part of the flight would be over the relative calm of the water, we could reverse the route and fly over the land first, when the turbulence should be minimal, and fly over the calm water later. He also mentioned that this would also fit in better with the tides and ensure that the Horizontal Waterfalls were working well when we flew over them. The change was universally welcomed, but Karen's fears of air sickness would soon prove to be well founded.

The plane was a six-seater - two seats in the front, two in the middle and two in the back. Seconds after take-off we passed over Birdwood Downs. I snapped a quick photo of the main house area as it disappeared beneath us, the yellow roofs of the huts a stark contrast to the surrounding green paddocks. Pretty soon the bump of Mount Hart appeared on the horizon and we made our way towards a station of the same name near the base of the mountain. The change of plan meant our scheduled stop at Mount Hart Station would now be made sooner rather than later. This would be a critical factor in the story of the flight.

On the "tarmac" at Mount Hart

After a brief tour of the station buildings and a talk on its history, we were ushered into the dining room of the homestead where a lavish spread awaited us. An all-you-can-eat morning tea was included in the price of the tour, and set out before us were three different types of cakes, plus a traditional Devonshire tea of scones, jam and cream. All four of us had more than our fair share of these culinary delights. Given our gluttony, we would probably have felt a bit crook afterwards anyhow, even without the additional discomforts caused by the flight.

The Mount Hart runway had only just been re-opened after heavy rains. Because of a boggy patch at one end of the runway, we were forced to take off downwind. Peter sat in the front of the plane with the pilot, with Karen and I in the middle row of seats and Mihkala in the back. We had also acquired an extra passenger at Mount Hart, a backpacker girl who had been working at the property and was now travelling on. As the pilot gunned the engine and we accelerated down the runway, all of us were wondering whether the extra weight would affect the take off. We were not left wondering for too long.

We hurtled along the bumpy gravel surface of the runway. The pilot seemed to be taking forever to get the plane in the air. The end of the runway was approaching fast. Anxiety levels in all the passengers, and probably the pilot as well, went through the roof. The scrub alongside the runway was going past at a furious pace. From my uninformed perspective we were going fast enough to become airborne, but the downwind take off meant we would have to be going faster than normal to reach the proper air speed. Just when we all thought we were dead, the plane jumped over the first line of scrub and continued to climb.

During the last few moments I can remember becoming very calm, thinking that if I survived the crash I would at least have an interesting story to relate. Fatalistically, I thought that if I died, then I died. My middle aged life had been pretty long and pretty good anyhow. In the front seat, however, Peter was thinking that he was too young to die. When the plane cleared the end of the runway and everyone realised that we had not crashed and that we were relatively safe, we all broke out into a cold sweat and laughed nervously. Peter also realised that the richness of the food at morning tea, the subsequent hairy take off, the heat of the cramped cockpit, the noise of the engine and the motion sensors of his middle ear had all conspired to make him feel pretty crook. He grabbed a sick bag and threw up.

The next inkling of potential calamity came a few moments later when the pilot produced a map from between the seats and proceeded to search the horizon for landmarks. He admitted that this was the first time he had flown the route, but tried to reassure us that he was an experienced pilot and expert navigator.

The Prince Regent River

We experienced a bit of turbulence as we crossed over rugged country and turned to follow the course of the Prince Regent River. Karen and Mihkala, both on the left side of the plane, noticed an attractive set of falls as we swung around, but said nothing. The pilot told us to watch out for a big set of falls somewhere along the river on the left. Karen tapped him on the shoulder and said that she thought we had already passed them, so the pilot consulted his map and then swerved around in a tight turn to head back up the river. This did not help Peter's constitution any. He was well into his second sick bag by now - completely wasting his morning tea.

King's Cascades

We eventually passed the King's Cascades for the second time, this time on the right. The pilot swung the plane around again, much to Peter's annoyance, and we passed the Cascades for a third time before continuing on our way. Our next destination was the famous Mitchell Falls in the middle of the Kimberley. More turbulence hit us over the plateau. The pilot was becoming a trifle concerned about Peter's continual spewing, and said we could pass over the Falls at either a low altitude for the view, or a high altitude where smoother air might alleviate Peter's disorientation. Peter was crook and unlikely to get any better so I voted for the view, but the girls were feeling motherly and had the numbers to say we climbed. To make their case even more water-tight, both Mihkala and our extra passenger picked that moment to chuck up as well. Women!

Mitchell Falls went by eight and a half thousand feet below us rather than fifteen hundred. Peter was asleep at the time, his mind and body deciding he had had enough. I zoomed my camera lens out as far as it would go in a vain attempt to capture an image of the falls. The photograph I took shows a dull blue squiggle passing through a hazy landscape of grey-brown and grey-green, three smudges of white indicating the drops of the falls. Bloody Peter!

Peter was still asleep as we passed over the magnificent table-top of Mount Trafalgar and made our way past Saint George Basin towards the Horizontal Waterfalls in Yampi Sound. The rivers and their tributaries spread through the tidal flats below us like the branches of the boab trees in the country beyond. With Peter almost catatonic, the pilot dropped down to fifteen hundred feet again for the fly-by of the waterfalls. The waterfalls were flowing rapidly through the narrow openings in the fingers of land which tried to hold the water back. As we approached the first time, Karen, Mihkala and myself all called out to Peter to wake him up, and he groggily lifted his head to gaze out the window at the objects of his childhood affections. The pilot made three passes along the area of the falls, with the gentle aerobatics of the turns churning up Peter's insides yet again until he chundered.

The Horizontal Falls

We stayed at fifteen hundred feet for the remainder of the flight as we passed over the mines and resorts on Koolan and Cockatoo Islands, and the rest of the "Thousand Island Archipelago". Eddies in the water told of the currents caused by the massive tides. Pearl farms disappeared beneath the wheels of the plane. The Marsh and Derby appeared to our left, then it was almost over as we made our final approach. Just before the plane touched down, Peter threw up again.

Karen's fears had been borne out. Surprisingly, she had not been the one to suffer, but she had still felt sorry for Peter during every one of his bouts of up-chucking. For Karen and I the flight had been excellent, but we both agreed that while it had been smooth, it had been too long a time to be confined in hot and stuffy cabin.

Back on the ground, Peter recovered quickly. We drove into Derby and bought lunch, eating it in the grounds of a park. During lunch we were joined by a couple of locals who came to sit and talk with us. The first was a drunken aboriginal male.

"What's the matter?" he said. "Haven't you ever seen a good looking black fella before?"

"No," I replied.

He wandered off a little bit later after he had got us all to agree that he was the best looking black fella we had ever seen. The second local was an aboriginal female the size of Uluru, but darker.

"I got no car," she said. "Can you give me a lift?"

"Sorry," Karen said. "I haven't got a car either."

"Can you give me some food?"

"No."

"Can you give me some water?"

"There's a tap over there near the wall," said Karen, pointing.

The woman left soon after.

We sat around reading the Sunday paper until near dusk when we walked out onto the Marsh to watch the sunset. Afterwards we adjourned to the town's outside picture theatre where we watched Dante's Peak, a disaster film about the effects of a volcano on a town. Peter thought that exploding mountains and rivers of lava which destroyed everything in their path were pretty tame after the traumas of his day.

Karen and Mihkala trying to get Peter to smile after the flight

|