|

Tom left the gaol before us the next morning but we passed him just before morning tea at Wirrabara. He in turn passed us a few minutes later. At lunch at Melrose, near the base of Mount Remarkable, we heard that he had taken off just before we arrived. We never saw him again.

Apart from Mount Gambier, the Flinders Ranges and maybe Kangaroo Island, South Australia is seriously lacking in the scenery department. Perhaps it is because the state is mainly desert, with hardly a river it can call its own. The Nelson river flows out of Victoria, takes one look at South Australia and flows right back into Victoria again! The Torrens River, the pride of Adelaide, looks great when it is dammed near the city, but it trickles into the Gulf of Saint Vincent via a glorified drain. And the Murray, arguably Australia's mightiest river, gives up the ghost after arriving in South Australia and oozes ignominiously into Lake Alexandrina with barely enough power or motivation to reach the sea.

Still, it is not as though South Australia has absolutely nothing. The Flinders Ranges are superb, and that was where Karen and I were heading. From Melrose we cycled another twenty four kilometres to Wilmington, where Karen decided she had had enough riding for the day. I wanted to push on to Quorn for a big day of one hundred and twenty five kilometres, but Karen vetoed that suggestion. While in Clare, Karen had rung the Quorn caravan park and arranged to leave our bikes there while we caught a bus to Wilpena Pound. She knew the bus would not be leaving until late the following day, so why bust our guts today, she argued, when a couple of hours of riding tomorrow morning would have us in Quorn in plenty of time? So we stayed in Wilmington. Sensible woman, my wife.

Wilmington is a little town with two caravan parks. I wish we had gone to the second one. The one we stayed at was a lot closer to the centre of town than the other, had good facilities, and an excellent recreation room which included a colour television, but in the middle of the camping area was a wood and wire construction that I had originally mistaken for a children's playground. It was not until dusk when a lady shepherded a few chickens inside it and locked them that I realised it was a chicken coop. I did not think any more about it, until 2:55am when the rooster started crowing. He was still crowing when we left the next morning, and I can vouch for the fact that he did not stop crowing all night long.

Prior to beginning our trip I would indulge in KFC at least once a week, and often more, but due to budgetary considerations the beautiful food of Colonel Sanders was no longer a part of my diet. While I lay in the tent, unsleeping, listening to that rooster crow, I wondered whether my previous consumption of his relatives had angered the chicken gods, for they certainly brought down their wrath upon me that night.

The forty two kilometres to Quorn only took an hour and three quarters the following morning. We had morning tea at the caravan park and confirmed our arrangement with the manager to leave our bikes in storage there while we bussed up to the Flinders. Karen and I were in constant wonder at the generosity of strangers like the caravan park manager. We had not even spent a night at his park, but already he was going out of his way to make our lives easier. Again and again we encountered similar kindnesses, and we have done our best to reciprocate.

We spent a couple of hours sorting out what gear to take and what gear to leave behind. At 3pm we stored our bikes and lugged the rest of our stuff into town and caught the bus. By the time we arrived at Hawker for a dinner of fish and chips at a brief stopover, Karen and I were already a little disenchanted with our new mode of travel. It was extremely frustrating to see unrecognised birds fly up from the side of the road, and not be able to stop to find out what species they were. Things got worse after Hawker, when an absolutely incredible sunset was happening outside the bus, yet we could not stop to take a photo. Two hours on a bus and already we felt that our freedom had been taken away.

It was dark by the time we arrived at Wilpena Pound. At the motel we asked where the camping ground was situated and we were directed to a shop across the road. A sign on the door of the shop directed us up to the campground. The night was very, very dark, with no campground lights and no moon - nothing but blackness. Without the weak light from our torch, we would not have been able to see anything. We stumbled around the campground trying to find a place to camp, eventually realising that there was no grass anywhere and virtually nothing to differentiate the camping sites from the roadways. I put the tent up in a small area surrounded by half a dozen thin and stunted trees, figuring the road could not possibly fit between them. In the morning when we could finally see where we were, we discovered that we had camped in an island surrounded by minor roadways, and we quickly moved to a more convenient site.

Our first day at Wilpena was fine and warm with scattered clouds. At the ranger station we bought a map of the Wilpena area and set out on our first walk shortly afterwards. Wilpena Pound is a vast bowl almost totally enclosed by rugged rock walls. A narrow ravine provides access to the pound on its eastern edge. We climbed up the outside of the rim to the nine hundred and forty one metre high Mount Olsen Bagge for spectacular views over the entire pound. It was easy to see why Wilpena Pound was once thought to have been formed by a meteorite impact, because it really does look like a huge crater. While returning to the campground, we detoured for an hour to follow the "Droughtbusters" nature trail - a self-guided walk with signs at various points showing the adaptation of the flora to the scarcity of water.

After lunch we walked through the access ravine to the historic homestead not far inside the entrance to the pound, climbing up to the Wangarra lookouts before returning. Dinner was cooked and consumed at the tables and chairs outside the shop, about a hundred metres away from our new tent site.

Olsen Bagge is south of the entrance to the pound, but the highest of the encircling mountains - Saint Mary Peak - is to the north. It was to be our destination the next morning. The walk led initially through a scattered pine forest on the outside of the pound before arriving at a rough, rocky trail leading diagonally upwards towards the rim. The morning mist soon cleared and we climbed in bright sunshine up to Tanderra Saddle, the last place I expected to find a new bird - the Shy Hystacola. Saint Mary Peak looked pretty rugged from the saddle, with two climbers making the going look difficult. Clouds repeatedly condensed and then disappeared around the top of the peak, adding to the atmosphere, but when we actually started to follow the track to the summit, we found the climbing no harder than many other rock scrambles we had done. The views north from the saddle and the summit were even more impressive than the views into the pound itself, with the jagged parallel folds of the Flinders Ranges disappearing away into the distance.

It was cool on top of the mountain, with a few spots of rain, so we quickly made our way back to the saddle, descending into the pound and following a dry creek bed through the lightly timbered interior. Red capped robins were everywhere and we passed a small herd of feral goats as well, eventually arriving once again at the homestead and retracing our steps of the previous afternoon out to the campground. We figured the round trip was about eighteen kilometres.

The following morning, after brief visits to the nearby resort and the ranger station, Karen and I decided to take advantage of yet another sunny day to walk through the middle of the pound to Bridle Gap, a dip in the western rim of Wilpena which mirrors the gap in the west. This simple walk, from one side of the pound to the other, and then back again, would take us the rest of the day and comprise a distance of about sixteen kilometres - not much shorter than the previous day's trek. Much of the day was spent walking through the uninspiring open woodland which makes up most of the interior of the pound, but the views from our lunch stop at Bridle Gap more than made up for the effort. A series of low, rounded ridges rolled away to the west towards the stark beauty of the Elder Range, a jagged ridge of purple and blue.

Karen and the Elder Range from Bridle Gap

With food running short and no more tracks to walk, Karen and I packed up our tent and sleeping bags the next morning after four wonderful nights at Wilpena Pound. The bus deposited us back in Quorn at lunchtime. We walked out to the caravan park, retrieved our bikes and pitched the tent yet again, spending the afternoon doing a load of washing and relaxing. We walked into town at dusk to have dinner in a local pub where we talked with another couple of cyclists who were following the Mawson Trail on mountain bikes. They were living a life of luxury every night in bed and breakfasts or pubs. I wonder if they detected our envy. It would be a nice way to travel if money was no object.

A cool, dewy night, undisturbed until 4am when the neighbouring dogs and roosters kicked in, gave way to yet another beautiful autumn day. The tent was still damp when we packed it up at nine and headed west towards the Pichi Richi Pass, the route off the Flinders Ranges down to the coast for both the road and the well-known tourist railway. A long and gradual descent brought us back to Highway One about six kilometres south of Port Augusta. We were soon checking into a motel on the northside of town, deciding to use the last of our vouchers on two days of luxury before journeying into the unknowns of the Outback.

Karen had phoned ahead to book the motel a week earlier, and Kevin had taken the opportunity to forward some mail to us. It was awaiting us when we arrived. One letter shocked us profoundly. Three years before, Karen and I had visited a solicitor and had our wills drawn up. It had been National Will Week at the time, or something like that, and solicitors around the country were waiving their fees for wills if their clients made a donation towards a major charity. The solicitor had taken down our details, made a few suggestions and we eventually agreed on the wording of the wills. After waiting a few days for the wills be prepared, Karen and I had returned to the office to have the wills signed and witnessed. We can still recall a secretary being called into the solicitor's office to witness the signatures. However, the letter we received at Port Augusta stated that our wills had never been signed! It included a copy of each of our wills, which were to be signed and returned at our convenience.

We were dumbfounded! As far as we were concerned, our wills had been signed and sealed. In the intervening period, Karen and I had cycled about six thousand kilometres on the busiest and most lethal highway in Australia, experienced wild storms at sea while sailing to Lord Howe Island, camped by rivers known to be infested with crocodiles, made numerous flights in some dodgy small planes, and worked with tractors and horses and snakes and spiders! We could have died on any number of occasions. And now the solicitor was telling us that our wills were not valid! The next morning we took the wills to the reception area of the hotel to have them witnessed.

"Um, excuse me, we're the people from unit number two," I said to the manager.

"That's right. Are you wanting to check out?" A disturbing phrase in the circumstances.

"No, we'll be leaving tomorrow."

"Oh, that's right. You're the bike riders, aren't you? Where are you headed?"

"We head towards Woomera tomorrow, into the Outback for the first time."

"Don't the roadtrains bother you?"

"No, they've been pretty good so far."

"Well, aren't you afraid of the crazies, the ones who roam the highway all the time, just looking for kicks?"

"No, we're always pretty careful."

"But what about water? Aren't you worried about dying of thirst?"

"No, we'll get plenty of information about the location of all the roadside water tanks. And there are always plenty of caravanners around to give us water if we get really desperate. We are pretty sure we've got that covered."

"I hope you have plenty of ambulance cover with you. Are you insured?"

"Yes, we are. With the distances out there, if we had no cover and had a serious accident, it would cost us a fortune for a trip to the hospital. So we made sure we joined an ambulance fund."

"Good. What about medical insurance? Are you in a top cover fund?"

"No. It doesn't fit in with the budget. And besides, if we get seriously hurt, we won't care which hospital we go to. The same with doctors. If we have an accident, it doesn't matter to us who treats us, just as long as somebody does. The government takes our money for Medicare anyway, so that is what we are in."

"You're both very brave, that's all I can say, but I guess that if the thought of dying was on your mind, you would not be cycling around Australia in the first place, eh?"

"That's right."

"Well, good luck to the both of you. Anyhow, what can we do for you?"

"We'd like you to witness our wills ..."

At Port Augusta Karen rang the Department of Main Roads, asking about information on parking bays, rest areas and water along the Stuart Highway. Within two hours we had the information in our possession, personally delivered by the public servant Karen had spoken with on the phone. Personal service above and beyond the call of duty from a government agency? Unbelievable!

Like all motel rooms, ours had a refrigerator, so we bought an extra luxury during our two days at the motel - a cask of white wine. We had a few glasses the first night and both of us fell asleep watching Essendon beat Geelong in the Australian Rules Football Centenary game. We finished off the cask on the second night of our motel stay, not wanting to carry its weight the next day, but not wanting to waste it either. Karen may have over-indulged, because shortly after the wine was finished, she realised she was drunk and threw up. It was probably a good thing that the alcohol was out of her system so early. The next day, along with me and a small hangover, Karen rode one hundred and three kilometres into a headwind and camped out in the scrub. My wife can be a very tough woman sometimes.

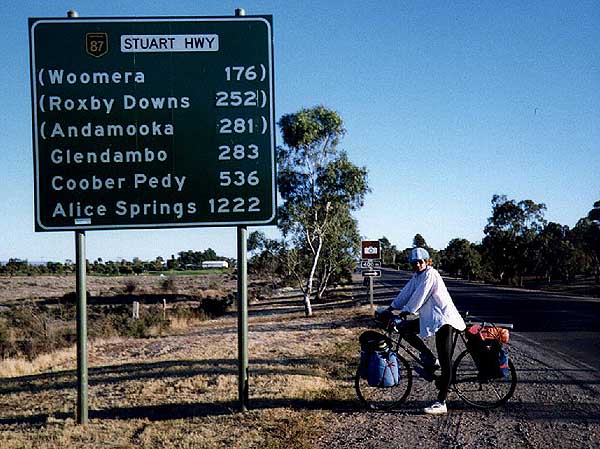

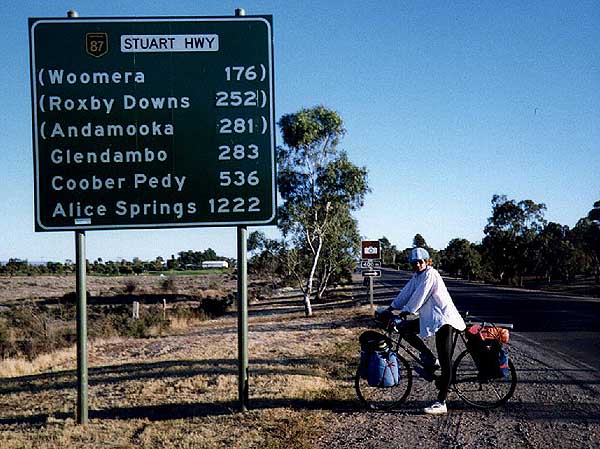

Our first day into the outback had started off slowly, with a fragile Karen refusing a hearty breakfast of spaghetti and meatballs and settling for a couple of pieces of lightly buttered toast instead, eaten between a litany of mumbled phrases in which the words "never again" were prominent. Just outside of Port Augusta we came to a junction where a classic sign gave us a simple choice - straight ahead for Western Australia or turn right for the Northern Territory. We turned right.

A long way to everywhere

Within a few kilometres the terrain had turned into desert. A long, steady hill led up onto a plateau. I pushed hard up the hill, leaving Karen in my wake, stopping at the top to remove my camera from the bottom of a pannier and take a shot of my struggling wife as she laboured towards the crest. The photo shows that Karen managed a smile, while in the background the road stretches through a barren, brown landscape.

Karen north of Port Augusta

Every kilometre, an ever-decreasing number on a roadside pole indicated the distance remaining to the Northern Territory border. The first one had been nine hundred and twenty seven. These would prove to be a valuable aid because the information we had received on water tanks and rest areas referred to each location by its distance from the border. Our lists assured us that water would be available at the eight hundred and seventy six kilometre mark, and it was accurate. Fifty kilometres north of Port Augusta, at a place where the Stuart Highway, the railway line and the water pipeline to Woomera all converge, we found our first water source - a valve in the pipeline where we filled our bottles and water bag in preparation for another fifty kilometres of riding and an overnight camp.

Filling bottles at the Woomera water pipeline

A steady headwind had us swapping leads every five kilometres throughout the day. Two new birds improved Karen's disposition - a Crested Bellbird and a few groups of Blue Bonnet Parrots. Lunch, of course, would improve Karen's disposition even more, so we stopped at the eight hundred and sixty six kilometre parking bay after about sixty kilometres of riding. Facilities at the parking bay were minimal - one garbage bin. We sat in the dirt and ate our lunch, watching hundreds of shredded pieces of toilet paper flutter in the wind in vain attempts to escape the clutches of the sparse grass stalks that had captured them. A truly idyllic scene.

Lunch in the dirt

Afternoon tea was twenty kilometres later at the eight hundred and forty six kilometre parking bay, and another twenty or so kilometres brought us to a parking bay and water tank at eight hundred and twenty five. The parking bay was deserted. There are no towns, roadhouses or dwellings anywhere near the highway north of Port Augusta, until you reach Pimba, one hundred and seventy three kilometres up the highway. If pushed, we could have ridden this distance in one hit, but the headwinds had taken their toll so we decided to set up camp.

For caravanners or campervanners, stopping overnight in a parking bay or rest area is a much safer option than it is for pushbike riders. The vans offer a fair degree of security, and if danger threatens there is always the possibility of driving away. A tent offers little security, and unless we were threatened by a pedestrian, there would not be much likelihood of being able to ride away from any danger. Later in the trip we would actually spend a night in a rest area, but only when a group of caravanners offered us the safety of numbers. Because the rest area north of Port Augusta was deserted, we decided to choose an alternate location to camp, but one not too far away, as the rest area had a water tank which would allow us to fill our water-bottles in the morning. I scouted the area and located a suitable camp site, then, after loading up with water for the evening's cooking, cleaning and consumption, we wheeled our bikes out to the highway and a hundred metres back to where a curve gave us a good view of the road in both directions. When no traffic was visible, we quickly pushed our bikes off the road and into the scrub.

Off road camping can be an extremely safe activity, as long as the campsite cannot be seen from the road, and nobody sees you on your way to it. Once there, I set up the tent and Karen cooked dinner before the sun disappeared for the day. After sunset we relied on the twilight, and later the light from the moon and stars. We kept our use of torchlight to a minimum, as we did not want to advertise our presence in any way at all. We know we have nothing to fear from almost all of the people who travel the highways of Australia. We also know that it is highly unlikely that the person who sees us on our way to our campsite will be sick enough to return to attack us later. Hundreds of people camp perfectly safely every night in full view of passing traffic. But there are some very strange people in this world. The trial of the Backpacker Murderer, and the massacre of thirty five people at Port Arthur would both occur while we were travelling.

A few days later, after another bush camp, we would return to the road the next morning and find a small memorial dedicated to a guy who had been murdered at that location only three years before. I am glad we had not seen the memorial prior to our first night in the outback. Karen would have heard the footsteps of murderers outside the tent all night long.

All of these kinds of thoughts were spinning around inside our heads when we crawled into the tent later that night. The winds that had plagued us during the day had gone. The air was still. Sounds seemed to travel forever. At first, we listened to the increasing volume of sound of every car approaching us on the highway, waiting for it to pass then listening again as it moved away and silence slowly returned. After half a dozen cars had gone by we were becoming accustomed to the sound and were slowly drifting off to sleep, when a new and different sound caught our attention. The first roadtrain of the night was approaching. It seemed to take forever to reach us. The sound of its engine must have been ear-shattering right next to the highway, but at our campsite, cushioned by two hundred metres of distance from the road and by a few stands of mulga, it was merely very loud.

A few more roadtrains came and went, and once again we were adjusting to the sounds of the night when the monotonous tone of an approaching car suddenly changed in pitch. We listened closely as the car slowed, and we heard the crunch of tyres on gravel as it turned into the rest area on the other side of the highway. Then the engine stopped, and we heard the sound of a car door being opened, and even the sound of a few footsteps. Then silence. . We knew we had nothing to worry about - nobody knew where we were - but try telling that to our rapidly beating hearts and our straining eardrums. We heard nothing for about three minutes, then came the sounds of a few more footsteps, the slam of a car door, the engine being started, and the tyres on the gravel as the car swung back onto the highway and accelerated away into the still of the night. Karen and I began breathing again.

This scenario was repeated at least a dozen times during the night, and we listened to all of them. It did not take us long to figure out that every man and his dog was pulling into the parking bay for a pit stop. There were no toilets there, just a big open area with a water tank in the middle of it, but that did not seem to deter anyone. It was a deserted area off the highway, so people used it. We were thankful we had chosen to camp so far away from it, though even at three hundred metres we could still hear every sound as clear as a bell. How far from the highway would we need to camp in order to have a silent night?

Next day we rode the remaining seventy seven kilometres to Woomera. In the afternoon we spent ninety minutes touring the town's scenic spots - which was probably about sixty minutes too many. That night, happily ensconced in the relative safety of a caravan park, we watched a south-westerly change blow into town, complete with thunder and lightning and the first rain Woomera had seen for eleven months. Lucky us.

Rocket park at Woomera

We had planned to leave Woomera the next day, but strong westerly headwinds which stayed around after the rain had gone forced us to stay in town another twenty four hours. We could barely contain our excitement. All day we could hear the one-horse town of Glendambo calling to us from one hundred and twenty one kilometres up the highway. If the next bit of bitumen had been north to south like the rest of the road we would have dismissed the westerly winds and gone full steam ahead, but Glendambo lies almost due west from Woomera, the only east-west section of the Stuart Highway in the three thousand kilometres between Adelaide to Darwin.

We would ride to Glendambo in one long and rather interesting day.

|